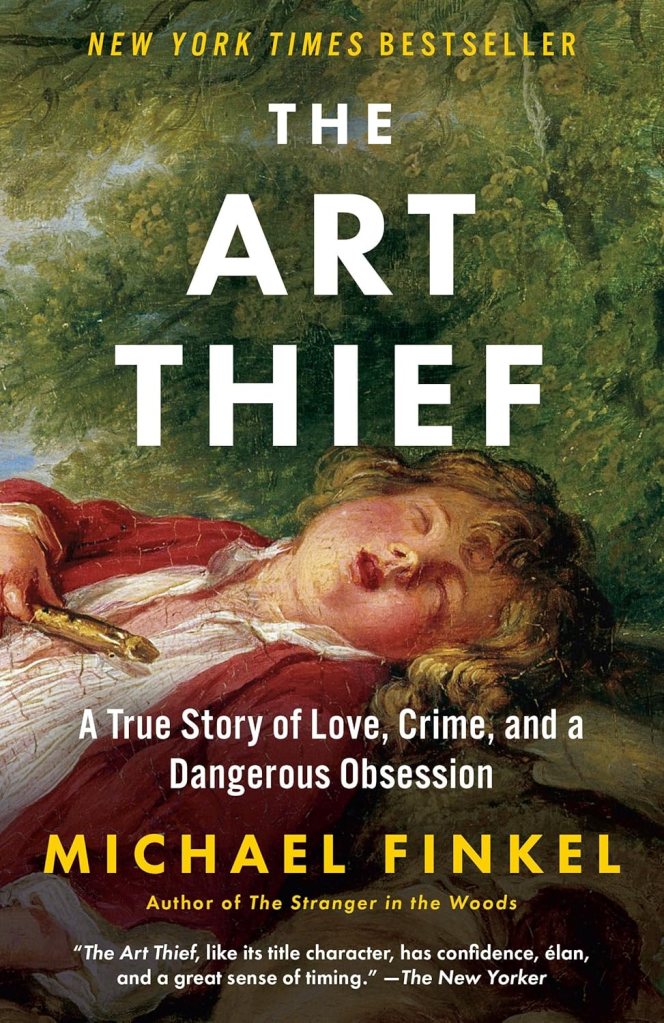

by Michael Finkel

I don’t read a lot of non-fiction, though I do like to add the occasional art book or historical account into the mix. Most recently I read The Art Thief: A True Story of Love, Crime, and a Dangerous Obsession, an account of the prolific museum stealing spree undertaken by a young Frenchman in the 1990s. The book provides a detailed account of many of the heists carried out by the man (and his girlfriend) alongside psychological analysis and art crime factoids.

Over the course of several years, Stephane Breitwieser, then a young man in his mid-20s, stole hundreds of objects from small museums across France, Switzerland, and several other countries. By the time his thefts were connected and uncovered, the total value of the objects was estimated at $2 billion. Despite the incredible monetary value attributed to his collection, Breitwieser never sold a single item he stole. Rather, he displayed the mass of objects in the small attic room above his mother’s house where he lived with his girlfriend, Anne-Catherine.

Breitwieser was a skilled and natural thief. He pocketed silver goblets and ornate tobacco boxes, tucked renaissance paintings under his jackets, and walked past guards with medieval weapons in his duffle bags. His girlfriend would keep watch as he casually pried open display cases, picked locks and scaled walls to retrieve whatever painting or objet d’art had become his latest fascination.

He was knowledgeable about the art he stole, and he collected with a shrewd eye and exquisite taste. He took 17th century ivories and 16th century silverworks. He took paintings by Cranach the Younger (from a Sotheby’s estate sale, no less), Brueghel the Elder, and van Kessel the Elder. He took an etching by Durer and early carvings out of churches. All of this he studied and kept, arraying his bedroom in finery.

When he was eventually caught and tried, in multiple countries, Anne-Catherine turned her back on him, saving herself by steadfastly maintaining innocence. Breitwiser caved during interrogation, confessing to the hundreds of thefts, even detailing how some of the heists were carried out. He served several years in prison, though it wasn’t long after his release that he went back for stealing again and again.

He first published a tell-all memoir with a ghost writer that was overshadowed by his reincarceration. He then kept out of the public eye and refused all contact with journalists, until, that is, he agreed to meet with Finkel.

Michael Finkel is an American journalist and memoirist. He wrote for The New York Times before being fired over a controversial choice in a 2001 story. He wrote a memoir about his relationship with another criminal (this one a murderer) in 2005. He has continued to write memoir style stories based on interviews, including The Art Thief, his latest work. The 2023 book was named Book of the Year by the The Washington Post, The New Yorker, and Lit Hub.

I personally felt that Finkel was a bit too generous in his depiction of Breitwieser. I by no means think the thief is an evil person, he never harmed anyone – other than the artwork – during his thefts that we know of, and he clearly has some sort of kleptomania or a similar disorder. However, I did not find him to be nearly so sympathetic a person as Finkel clearly felt he was. Finkel was clearly charmed by Breitwieser over the course of their interviews while writing the book.

Great paintings transport you to a place of luminance and memories. Inside of paintings is where I keep my second home.

As an art historian myself, I understood the thief’s love for the artwork and the covetousness the works can inspire. It was posited that the young man felt a sort of mania when he was newly enamored with a work of art, such that he couldn’t help himself from taking it into his hand and carrying it home. He truly felt (or so he claims) that was he was doing was right, that he was protecting the artwork and giving it a home where it would be truly cherished.

As a museum professional, I was furious that he thought a private home was a better place for these objects to be stored. His selfishness, disguised as passion, resulted in the public completely losing access to these artifacts and artworks, some for a few years and some permanently. He didn’t protect the art, he damaged and ruined multiple pieces due to improper storage and carelessness.

And worst of all, the reason I did not find him to be sympathetic at all, was his complete lack of remorse. He saw no issue with what he had done. He did not truly grieve the loss of objects and paintings. He prioritized his own greed over the art and he never thought he did anything wrong. And even after the massive pile of loot was discovered, he eventually continued with petty thefts just to stretch his itchy, thieving fingers.

I definitely recommend picking up this book. While I may not have liked the light Finkel painted Breitwieser in, I loved the way he writes. Whether you enjoy art and museums, true crime and heist stories, or just nonfiction generally, I think you’ll like this fast paced foray into art investigation.

Leave a comment